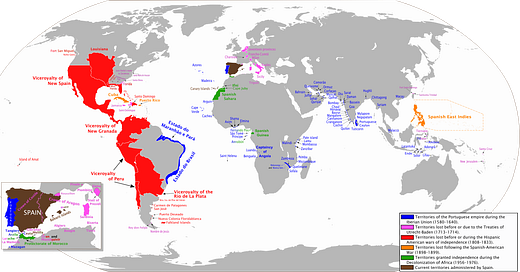

The Conquistadors followed hard on the heels of Columbus. There are books upon books written about them, their conquests, and their atrocities throughout the New World. They conquered the Caribbean, all of Central America, large portions of South America, all of Mexico, and a good portion of what would later become the United States. They claimed even more territory than that -see the map below for an idea of the extent of the Spanish Empire.

This lesson is going to focus on a top-level view of those who entered the territory that would one day become the United States, as that is the primary focus of this series. Typical American history lessons skip from Columbus to Jamestown, 1492 to 1608. Some books will off-handedly mention a few of the other European countries that attempted to conquer and settle the lands that would become the U.S. over those 116 years, but it’s usually Columbus and then John Smith.

First among the attempted colonists were the Conquistadors.

First, What They Weren’t

Explorers. The Conquistadors are often listed as “soldier-explorers” or “explorer-soldiers” in textbooks and history lessons as if they were some more militarily minded version of Lewis and Clark. This is patently false. They didn’t care about exploring. They came to conquer land and find riches, especially gold, that they could steal and take back to Spain. End of story.

Who Were The Conquistadors?

They were Spanish and Portuguese soldiers sent out to conquer new lands and find new wealth for Spain and Portugal. They managed to conquer most of Central and South America, large portions of North America, and parts of Asia, Africa, and Oceania. They created the largest empire in human history (at that time) and sent enough looted wealth back to Europe to destabilize entire economies. Their success also spawned a wave of imitators.

The Conquistadors were not nice people. Granted, most conquering armies aren’t, but the Conquistadors were especially brutal. They destroyed multiple societies and civilizations. They brought down the Aztec Empire and razed Tenochtitlan. They conquered the Inca Empire. As they did so, they enslaved, murdered, tortured, and raped the indigenous population and committed genocide on a massive scale. One of the terrors of their expansion was the attack dogs they used on their opponents, in battle and out. I’m not talking about fluffy little poodles here, but giant war dogs trained to rip people apart.

We know these things as fact. They are not speculation or half-remembered oral stories. We know much of this information from the journals of the Conquistadors themselves and the missionaries and priests sent with them and after them. They didn’t think there was anything wrong with what they did, you see (well, some of the missionaries did, but not the soldiers themselves), so they didn’t think they needed to hide it or downplay it.

Don’t believe me? You don’t have to. You can read their accounts for yourself if you would like. Digital and printed copies are easily accessible. Many of them are in the original Spanish, but you can find translations.

“An account of the first voyages and discoveries made by the Spaniards in America : containing the most exact relation hitherto published, of their unparalleled cruelties on the Indians” by Casas, Bartolomé de las, 1474-1566

The Conquistadors were so wide-ranging in their “explorations” (read: quests for gold, jade, etc.) that they eventually reached but did not conquer or settle Alaska. By 1580, the Viceroyalty of New Spain encompassed all of Mexico, most of what would become the United States, and part of Canada. They never settled all of these lands, of course, but they had a presence.

How did they conquer so much land and take down so many peoples? Partly it was force of arms; they did have guns, armor, and swords, after all, which the native people lacked. But keep in mind they should have been severely outnumbered, and it doesn’t matter what kind of weapons you have if you’re outnumbered 10 to 1 or 20 to 1, or more likely 100 to 1. They did have some help from ostracized native societies they recruited, but that also wasn’t enough to help them succeed.

So, what was the real reason they were able to dominate so much of two continents? One word: germs.

The Americas had been separated from Europe for so long that the people living there had no experience with -and thus no immunity from -the many diseases European people had lived with for centuries. Even things such as the common cold and the flu proved fatal to some people who had no immunity to them, and those were far from the only diseases that came over with the Europeans. Others included smallpox, typhus, and dysentery. Native people died in wave after wave of these diseases for centuries, and it was disease that reduced their numbers and made it easier for the Conquistadors to make their conquests.

Had germs not hitched a ride along with the Conquistadors, the Spanish conquest of the New World might have ended the way Vinland did for the Vikings -in a humiliating defeat at the hands of Native Americans.

Conquistadors in the U.S.

Many Conquistador expeditions entered what would become the United States. There are too many for me to cover in such a short space, so I’m just going to discuss a few of the most famous. Each has been named for its leader(s).

Coronado

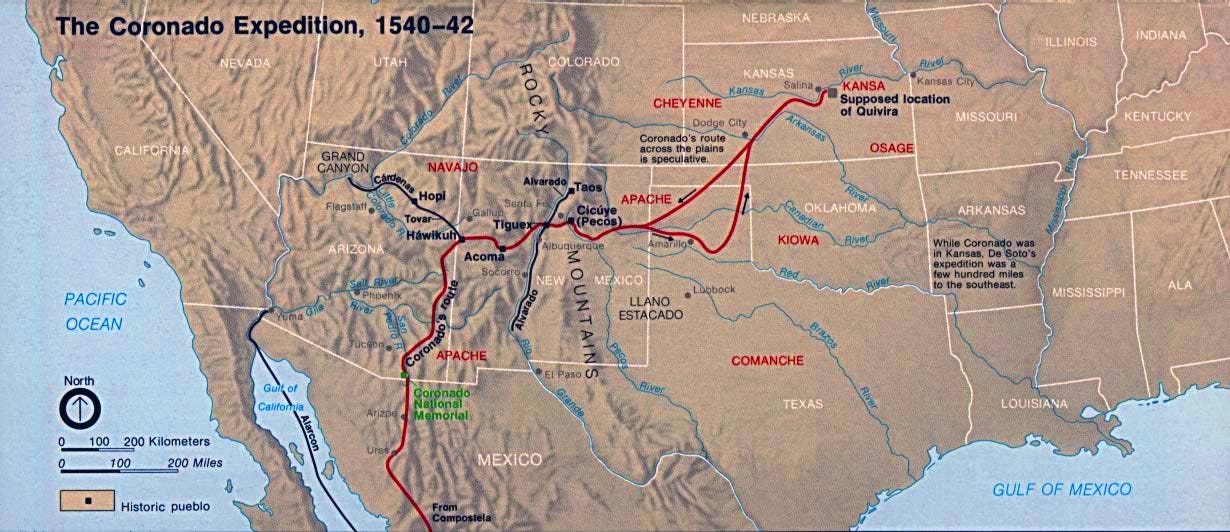

The Coronado expedition set out looking for the 7 Cities of Cibola, which myth held were made of gold. Presumably, he wanted to raze the cities for the gold and take over the mines where the gold came from. He returned to Mexico City (which the Conquistadors built atop the ruins of Tenochtitlan) empty-handed because you can’t build cities out of fucking gold.

In the meantime, between 1540 and 1542, he tooled around present-day New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Naturally, they used force to take what they wanted from the natives, including commandeering some of their villages for winter quarters.

Here’s a map of his expedition.

Source: U.S. National Park Service, 1974

Ponce de Leon

This man led multiple expeditions. He apparently liked doing it. He conquered and started Spanish settlement of Puerto Rico in 1508-1509. In 1513, he went on his first expedition to Florida, seeking the Fountain of Youth. He didn’t find that, but he did find the Florida Keys and land near present-day St. Augustine.

A few years later, in 1521, he returned to Florida with a mandate to conquer and settle the peninsula. He also wanted to search more for the Fountain of Youth. Unfortunately for him, all he found was a fatal arrow wound in a native attack.

De Soto/De Moscoso

The de Soto/De Moscoso expedition set out from what would later become Florida in 1539. The three-year expedition crossed portions of nine American states and conquered and fought with natives all along the route. They saw the Mound Builder cities in Mississippi and sailed down the Mississippi River on homemade boats. Many of this expedition died along the way, including de Soto. It had a fortunate outcome for the natives, however; the failure of this expedition to locate gold and wealthy cities convinced the Spanish not to explore the northern frontier further for some time. It would be another forty years before the Spaniards sent another expedition north, and this one would be looking for missing missionaries.

After their failure to find gold, the pullback of the Spanish allowed a power vacuum (in terms of European countries) to develop in North America, which other European powers were happy to exploit. They still claimed land in what is now the United States, but most of the people who ventured into the area for the ensuing four decades were missionaries. When the Spanish again began to venture northwards, it would be to conquer and settle. By the time the first ship arrived at Jamestown and the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, there would be two generations of Spanish settlers living in the American Southwest. That’s the subject of the next lesson.

Further Reading

· Journals of individual conquistadors and missionaries

· Conquistadores: A New History of Spanish Discovery and Conquest, by Fernando Cervantes

· American Colonies, by Alan Taylor

Looking back over the post, I noticed the caption on the first picture didn't transfer properly. It's found multiple places online and I could not locate the original source.