Lesson 4: Spanish Settlement in the United States

The English colonies may have formed the nexus of what would later become the United States, but they were relatively late in founding their first colonies in the Americas. The Spanish founded St. Augustine, Florida, the first permanent European settlement in what would become the U.S., in 1565.

Why Florida and why St. Augustine? It was mostly a response to a French outpost built nearby. The Spanish couldn’t have that, so naturally, they sent some conquistadors to massacre the French and found a settlement to take control of the area. They ventured as far north as present-day South Carolina before being pushed back by rightly pissed-off natives.

Spain’s Florida colonies never did thrive; they mostly used Florida as a buffer against other European powers and devoted most of their resources there to proselytizing the natives and converting them to Catholicism in hopes of making them into allies. They would later betray those allies, but that is another story.

The southwestern colonies got started because people were seeking more gold and silver. A group of Spanish colonists led by a conquistador named Onate settled in New Mexico in 1598. Tensions soon developed with the native Pueblos, mainly because the Spanish seized one of their towns for their own use and evicted the residents. They renamed it San Gabriel and began appropriating everything they needed for subsistence from the other natives.

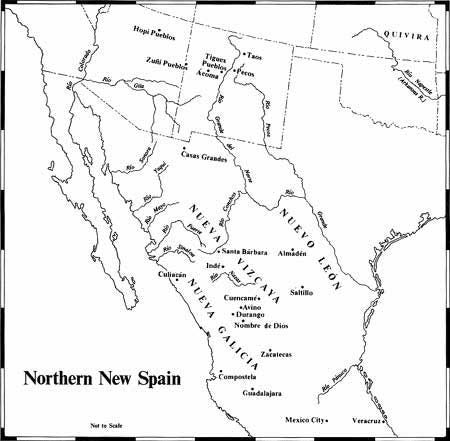

The northern frontier of Mexico, circa 1600, courtesy of National Park Service

When the locals from the pueblo of Acoma got fed up and resisted, Onate decided to make an example of them. They stormed the pueblo and killed hundreds of men, women, and children during intense house-to-house combat. The 500 survivors were then tried for “treason” by the Spanish, who condemned everyone over the age of 12 to serve as slaves for 20 years. Males 12 and up had a foot cut off to keep them from fighting back or fleeing.

Onate was rather magnanimous towards the captured children under 12. He found them innocent and sent them south to Mexico to be raised as servants in good Christian families. Onate wasn’t much better towards the colonists he was responsible for, but it wasn’t until he alienated the Franciscan missionaries with his treatment of the natives that anything happened. They could complain to the viceroy, and in 1614 he was found guilty of abusing both his charges and the natives and banned from New Mexico.

New Mexico grew slowly in the 1600s, but it did grow. The Pueblo people, already reduced by disease in 1598, were not so lucky. They slowly dwindled from 60,000 in 1598 to under 17000 in 1680.

Taos Pueblo, one of the few left standing, courtesy National Park Service

Native peoples rebelled against Spanish rule numerous times in the 1600s, and all the rebellions were eventually put down, but just before 1700, the Spanish and Pueblo people were forced into an alliance for mutual protection against the nomadic tribes of the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains. These people had no love for the Spanish, but they did love one thing the Spanish brought with them.

Horses.

By the end of the 1600s, these people would acquire enough horses from the Spanish by theft, purchase, barter, and other means to mount themselves and form an effective fighting force. They would quickly grow their newfound power into the Comanche Empire, which covered much of the Great Plains until the post-Civil War era. (Never heard of the Comanche Empire? We’ll get there.)

While English colonists were still getting a foothold on the Eastern seaboard, the Spanish were settling the Southwest. Before the Revolutionary War, they had begun settling in Arizona, California, and Texas. The first permanent European settlement in Colorado (then in New Mexico) was founded at San Luis in 1851.

Put another way, the Spanish had been permanently in what would become the U.S. for more than 250 years before the first shots were fired to start the Civil War.

France, the Netherlands, and Sweden also laid claims to parts of North America. The latter two arrived about the same time as the English, but the French had been here long before.

We’ll get to them soon. Next up we’re going to talk about the “Columbian Exchange” which is such a big part of many history units of this era, and what it really meant, including what it meant for the indigenous peoples of North America.

Further Reading

· American Colonies, by Alan Taylor

· The Comanche Empire, by Pekka Hamalainen

· A Forgotten Kingdom: The Spanish Frontier in Colorado and New Mexico, 1540-1821, BLM Cultural Resources Series (Colorado: No. 29) (free online!)

· Journals of the Conquistadors, early Spanish settlers, and missionaries.